As we discussed in our previous article, China is aiming to re-create Marco Polo’s ancient Silk Road, the trade route that once ran between China and the West during the Roman Empire.

The initiative is in many ways natural for China, the world’s largest commodity trader. But governments from Washington to Moscow to New Delhi are concerned that Beijing is also trying to build its political influence and erode those of other countries. Yet others are concerned that China might undermine human rights, environmental, standards for lending or leave poor countries burdened with debt.

India is particularly concerned that Chinese state-owned companies are working with the Pakistan-occupied Kashmir and see that as an endorsement of Pakistani control.

Pakistan’s Minister for Planning, Development and Reform Ahsan Iqbal says the proposed China-Pakistan Economic Corridor will turn bilateral “friendship into a strategic economic partnership.“ Indeed, if the scheme was implemented successfully, it would add an important economic dimension to the already close political and military relationship between Islamabad and Beijing.

For all these reasons, the Indian government have made a decision to counter China’s Silk Road by creating a new cross-continent plan of its own.

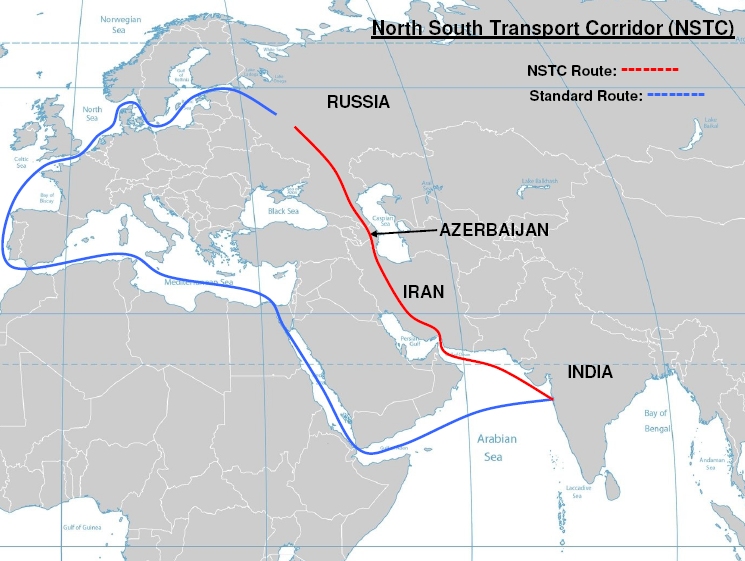

The North-South Transport Corridor (NSTC)

The New Indian Silk Road project name is the North-South Transport Corridor (NSTC), and it aims to better link India in with Iran, Russia, the Caucasus, and Central Asia.

At its core, the NSTC is a 7,200-kilometer multimodal trade corridor that extends from India to Russia, linking the Indian Ocean and Persian Gulf to the Caspian Sea. Goods travel by sea from Jawaharlal Nehru and Kandla ports in western India to the port of Bandar Abbas in Iran, then go by road and rail north through Baku to Moscow and St. Petersburg and beyond. A prospective second route goes along the eastern side of the Caspian Sea, moving up the new Kazakhstan-Turkmenistan-Iran railway and integrating with the North–South Transnational Corridor.

The main route of the North South Transport Corridor.

“The route has the potential to cut the Mumbai to St. Petersburg journey in half,” explained Jonathan Hillman, the director of the Center for Strategic International Studies Reconnecting Asia division. “By some estimates, the North-South route is even more economically promising than some emerging East-West overland routes.”

“The route has the potential to cut the Mumbai to St. Petersburg journey in half”

-Jonathan Hillman

Economic Potential

India, due to the size and pace of expansion of its economy, could potentially be the biggest recipient of Chinese investment from the plan to spur trade by building infrastructure linking Asia with Europe, the Middle East and Africa, according to a Credit Suisse report released before the summit.

Chinese investments into India could be anything from $84 billion to $126 billion between 2017 to 2021, far higher than Russia, Indonesia and Pakistan, countries that have signed off on the initiative, it said.

China is also conducting feasibility studies for high-speed rail networks linking Delhi with Chennai in southern India that would eventually connect to the modern day “Silk Road” it is seeking to create.

But if India continues to hold back from joining China’s regional connectivity plans the commercial viability of those plans will be called into question, analysts say.

If India continues to hold back from joining China’s regional connectivity plans the commercial viability of those plans will be called into question

Why India Is Wary of China’s Silk Road Initiative

India has other worries over China’s growing presence in the region, fearing strategic encirclement by a “string of pearls” around the India Ocean and on land as China builds ports, railways and power stations in country such as Nepal, Sri Lanka and Bangladesh.

Indian analysts are also concerned about a lack of operational detail.

This lack of detail is a major problem for Chinese policymakers who are keen to market the initiative. President Xi announced the ambitious program at the end of 2013 but after nearly four years we have not yet seen any detailed operational plan.

The current strategic mistrust between Delhi and Beijing will make it very difficult for Indian policymakers to accept the “One Belt, One Road” initiative in its present form. Rajni Bakshi, a senior Gandhi Peace Fellow from Mumbai’s Gateway House, has argued that Beijing has to co-design the new Silk Road with India for it to have any chance of success. If the Chinese government wants to address the trust deficit and get a larger buy-in from Indians, it will have to engage Delhi in the design and implementation.

Notes

India’s ‘new Silk Road’ snub highlights gulf with China

India Builds Highway to Thailand to Counter China’s Silk Road

India Is Building A ‘New Silk Road’ Of Its Own

Why China’s ‘Silk Road’ plan has spelt unease for India, US, Russia