Inflation expectations and inflation are mutually reflexive

If there is one phrase to sum up what we think has been happening in the markets since the US election, it is that inflation expectations and inflation are mutually reflexive. We believe reflexivity is true to different extents for many dynamics in the financial markets, and we believe it is one of the primary drivers for coming inflation.

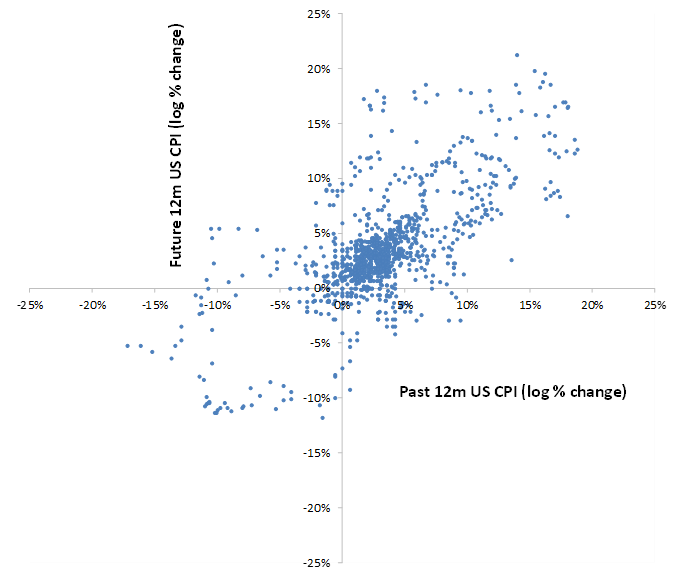

The following is a scatter graph of 12-month future US consumer price changes (logged) plotted against 12-month lagged US consumer price changes (again logged). There is no overlapping information between the past 12m and the future 12m represented by each blue point. The Consumer Price Index (CPI) data used is monthly from January 1914 to November 2016. There was only one clear outlier year, which was 1920 after World War I, and this was removed from the graph. The result is still over 100 years of inflation data in this analysis spanning approximately 20 different market cycles.

The R-squared of this auto-correlation is 0.47. Put another way, almost 50% of the future 12m inflation movement is explained only by knowing the last 12m inflation movement. Adding another simple step on top of this quant analysis (explained on request), it is possible to clearly show this auto-correlation is mean reverting, with a neutral equilibrium point approximately at 3.5% per annum. In other words, inflation below 3.5% (currently it is 1.7% at time of writing) tends to move higher the next year, and inflation above 3.5% tends to move lower the next year. This relationship of course overshoots significantly as observed, the full range of US inflation historically has been from -20% to +20% per annum.

Coming from a disinflationary mindset after the 2008 credit crisis, the market needed to “switch” into an inflationary mindset, and once this happens it would then tend to stay persistent. Of course, it was not President-elect Trump’s policies that caused this market switch, as he stated no workable policies. However, as it turned out during price discovery after election, the aggregate of every market trader’s own imaginary world of a Trump presidency was net inflationary. The overall market needed the idea of a seismic landscape shift like Trump to make its own switch into inflation expectation.

Shorting treasuries makes money, but requires tactical trading

The disinflationary period after the crisis was extremely good for bond prices, and the extensive negative yields were a testament to that. The reversal post US election back to inflationary expectation is similarly bad for bonds. Our positioning on bond duration has been negative since mid-last year. We believe that shorting duration must be traded tactically, because it is normally an anti-premium. However, we did hold and continue to hold negative yielding treasury shorts as a yielding premium. There will be times when duration participants, principally pension funds, find new higher yields attractive and purchase duration causing yields to drop. We vary our short duration exposure dynamically depending on market sentiment, from zero shorts to shorts of up to 30% notional for any one government issuer.

In terms of equities and corporate growth, the move from expectation of a disinflationary to an inflationary environment has been good for equities, despite the substantial set of systemic risks posed to growth globally. It is possible for business profit margins to stay ahead of inflation, and therefore equities tend to perform well in nominal terms relative to other traditional investments. Our position on equities since launch has been positive, although moderately so. However, we rapidly shifted the makeup of our equities from benchmark exposures to deep value and growth-at-reasonable-price equity names that are well capitalised and liquid. We believe that these types of equity premium factors will contain the more resilient profit margins in a reflationary setting, and the low valuation (typically P/E less than 10) provides some buffer during coming equity drawdowns.

In addition, we have strongly favoured commodities and commodity related equities. We continue to tactically take long exposure in specific commodities, such as within energy, agriculture, and more recently since the US election, base metals. The concern for many investors with commodities is the level of day to day volatility that they tend to provide. However, we manage risk exposures based on expected drawdown and not volatility, and as such, we can take relatively more volatile components when we are confident the potential net drawdown is contained within our expectation.

Commodities tend to show a lower ratio of future 6-year loss to past 2-year annualised daily volatility (a ratio typically lower than 1.5, calculation methodology available on request), i.e. although the day to day volatility might be high, the actual future loss that comes with it, relatively speaking, is not expected to be high. This requires careful sizing of our exposures, which we do by using Expected Drawdown Management. Conversely, high yield bonds, real estate equity and emerging markets tend to have higher ratio of future 6-year loss to past 2-year volatility (typically higher than 1.5), and these asset classes have been regular traps for investors in past cycles.

The potential systemic risks to global growth have grown in 2016 and are substantial. This includes European banking credit risks, emerging market credit risks and US high yield credit risks. We have held no exposure to these since launch, and expect to hold none until there is a significant repricing. We do not expect to hold shorts in this space, as shorting these premiums tend to be costly despite skewed risks to the downside. However, credit risks are not the largest underlying source of systemic risks this cycle, especially given the switch to an inflationary world. We perceive the largest systemic risk to be the reversal of global cooperation.

What does the word “cash” mean now?

It has been strikingly clear that 2016 was marked with the highest level of political risk since the end of the Cold War in 1991. We expect this increasing trend to continue for the long term and to observe future erosion in global cooperation that had been built up since the end of the Cold War. This global cooperation has been one of the key beneficial deflationary pressures, because along with global cooperation comes efficient global trade.

Cheap imports and profitable exports has raised the average living standard globally. However, as with all historical periods of such prosperity e.g. the Gilded Age of the late 1800’s, this average does not reveal the spread of those benefits, which is typically uneven across the social strata. This is one of causes of the social imbalances resulting in the recent shocks to the democratic landscape, whether it is the US election, UK Brexit or Italian No vote. However, as we see from the market pricing, these outcomes are not necessarily negative overall.

This is because they help write a new social contract and provide a release valve for the imbalances, which can be net stabilising rather than destabilising. The risks then come from non-implementation of appropriate change. If, despite expectation of otherwise, Brexit leads to no material change for the populous in the UK, or Trump leads to no material change for the populous in the US, we will see a resurgence and significant increase in political risk in the respective countries. Other European countries all have their own challenges in this regard, as do most emerging countries. The effect is less visible, but usually more explosive, in nondemocratic countries.

Of course, these structural changes required are typically not good economically, particularly to existing capital holders. The risks to accumulated capital are now many. With decreasing global cooperation, the first to go will be trade deals and we will see increasing trade barriers, as often touted by Trump. Trade barriers mean inflation in local currency and capital held in such local currency will be impaired, e.g. the fall in the pound after Brexit. There is also the risk of significantly increased taxes in the future, both corporate and personal, to cover deficits. These can be direct rate increases, or they can be through re-interpretation and enforcement of ambiguous tax code. Higher taxes will mean lower corporate valuations. Inflation will also mean increasing rates and declining treasuries value along the rates curve. Cash itself of course will no longer be able to purchase as much.

It is no longer clear that “going to cash” will be the safest investment holding. Our strategy focuses on growing the buying power of the fund’s capital base, and if the local currency (US dollars, euros) is under inflationary pressure and traditional bonds and equities are similarly impaired, the long term safest investments can be non-traditional investments that maintain daily liquidity during market stress. Shorting bonds as discussed is one of these, as is buying commercial commodities such as agriculture and base metals, all sized appropriately to control drawdown risk. We also diversify our fund cash exposure across long euro, long US dollar, long gold and long developed commodity currencies (Canadian dollar, Australian dollar and New Zealand dollar).

Non-cyclical investing of the fund

Another component of these alternatives are dynamic trading strategies. Model driven dynamic strategies have had a difficult time navigating the central bank maintained world since the credit crisis, but with the recent switch to an inflationary mindset, these strategies are more likely to provide a genuinely diversifying return component. Model driven strategies such as momentum tend to perform poorly during periods of quiet markets, but can provide very significant upside and protection during crisis periods. Currently around a quarter of the fund’s risk is in momentum related strategies to protect against sustained traditional market drawdown.

We also implement other dynamic strategies. One such strategy is a short-term cycling of equity volatility premium. Options markets are used to provide insurance against losses, with a significant premium income available to those who provide this insurance. Our volatility premiums strategy is discretionary and selective, waiting for times when the premium has spiked to a high level for either individual listed names, sectors or indices, at which point these outsized premiums are captured with contract maturity no farther than 2 months out. When premiums are low, the strategy stays quiet, holding little risk, and therefore minimises possibility of mark to market losses in any future volatility spike. Our options are written significantly out of the money, and we set the strike based on the Expected Drawdown of the underlying.

This is different from how options are typically priced by the option market, which is based on realised and implied volatility. As discussed, we believe there can be substantial departures between what volatility suggests as risk and the actual drawdown risk that can happen. We tend to select option underlyings where the ratio of expected future loss to historical 2-year volatility is unusually low. In this market of increased volatility-of-volatility, discretionary short term cycling of volatility premium we believe will be valuable income, with a much better liquidity and risk-return profile (“Premium Ratio” in Expected Drawdown Management terms) than traditional credit risk premium.

We use the term “non-cyclical” as it best describes the overall outcome of combining into Liquid Premium all our strategies discussed above. Using Expected Drawdown Management and a long-term view of the future market cycle, we actively move to negate the coming large drawdowns that we see impacting the majority of other capital holders. We also make sure that returns of Liquid Premium will be generated by market reversions to equilibrium states rather than relying only on continued valuation growth and global stability to do so.

Chi Lee